Goal Dependent Categorization

Up: AI and CogSci | Previous: Non-Axiomatic Reasoning | Next: Summarizing 20th century discussions

There seems to be a recurring theme that conceptualizing, categorizing, and reidentification are at the core of intelligence. Unless a system is able to reidentify new high-dimensional sensory data in terms of its previous sensations, every sensation of the system will be distinct and the system will be unable to make use of its previous knowledge and experience.

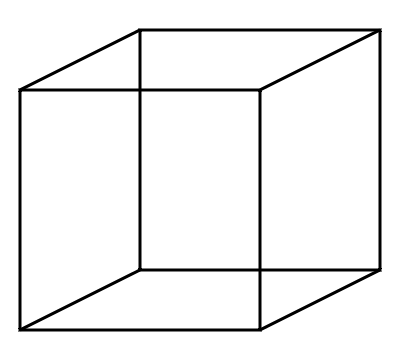

Usually, categorization and classification is based on closed world assumptions. But even a mere open world assumption does not suffice, because the way we categorize the same sensory experience depends on not just our own prior knowledge, but also on our goals and intentions. A relevant example concerning this is Necker's cube. (But also see other ambiguous figures in psychology.) The perceptual object (usually two) that one experiences, depends on which of the middle two vertices the observer focuses their attention on.

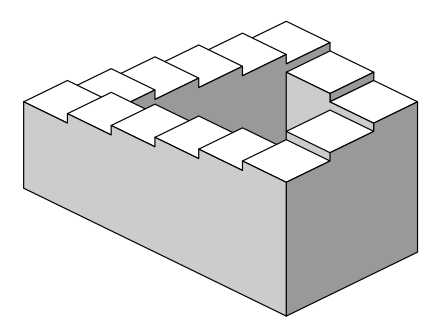

It turns out that in visual perception (atleast as understood around the early 2000s), attention - or rather foreground vs background - closely relates to perceptual depth. In particular, objects in the foreground (or near the foreground?) of our perception appear closer than objects in the background. Thus, a machine learning approach trying to obtain embeddings out of 2D images should also use a "perceptual" depth map in addition to the image itself. "Perceptual" because obtaining an objective depthmap out of 2D images is an underconstrained task, and as the example of the Necker cube above shows, a single 2D image can lend itself to multiple perceptions and accompanying depth maps. Perhaps, the idea that we perceive a global depth map also needs to be thrown out, because we can also perceive contradictory perceptual objects such as the Penrose stairs below. For me, these ideas first became concrete through a course on Visual Perception under Prof. Devpriya Kumar at IIT Kanpur.

Thus, one remarkable property about the mapping between a high dimensional stimulus and the high level categories is that this is a many-to-many mapping. In other words, the answers to questions such as "Who is this person?", "What is this an image of?", "What does this text mean?" depend on not only the thing under consideration, but also on who asks the questions, what categories the asker has in their mind, and perhaps what implicit or explicit goals or intentions the asker has.

When in danger, you can hit someone with a shoe in self-defense. Does it remain a shoe, or does it become a weapon then? The category corresponding to a particular high dimensional stimulus is not only dependent on the stimulus itself but also what the system itself is looking for. I have only come across Slot Attention which seems to acknowledge this. Even then, it's not really clear if and how this problem is or can be solved.

It turns out that this notion of "looking for" has already been discussed in the 20th century.

Up: AI and CogSci | Previous: Non-Axiomatic Reasoning | Next: Summarizing 20th century discussions